Op het einde van de maand brengen we het overzicht van de boeken-aanwinsten.

Volksmacht op Cuba. artikelen, toespraken en intervievs over binnenlandse en buitenlandse ontvikkelingen van de Cubaanse revolutie, Cubagroep Deze Vereldcentrum i.s.m. Venceremos.

Enver Hoxha, Le socialisme en Albanie 1, Union générale d'éditions, 1974.

Enver Hoxha, Le socialisme en Albanie 1, Union générale d'éditions, 1974.

Fidel Castro en Ignace Ramonet, Fidel Castro My Life. A Spoken Autobiography, New York, 2008.

Dienst Monumentennzorg en architectuur stelt zich voor in 2012. Lezingen, Gent 2013.

Dienst Monumentenzorg en Architectuur, Lezingen 2013, Gent, 2014.

2.28.2017

2.27.2017

'Arabian Nights'

Maandag, filmpjesdag. Vandaag brengen we een tamelijk vakidiote lezing.

Het Amerikaanse Penn Museum heeft niet alleen zeer boeiende lezingenreeksen, over zeer uiteenlopende onderwerpen, ze heeft ook de excellente gewoonte om die lezingen integraal op te nemen en op youtube te zetten.

In 2015-2016 liep een reeks 'Great Myths and Legends'. Het onderwerp van de lezing van vandaag is 'De Arabische Nachten'. Duizend-en-een-nacht en andere vertelsels.

meer:

Penn Museum en op youtube

dr. Paul M. Dobb

Het Amerikaanse Penn Museum heeft niet alleen zeer boeiende lezingenreeksen, over zeer uiteenlopende onderwerpen, ze heeft ook de excellente gewoonte om die lezingen integraal op te nemen en op youtube te zetten.

In 2015-2016 liep een reeks 'Great Myths and Legends'. Het onderwerp van de lezing van vandaag is 'De Arabische Nachten'. Duizend-en-een-nacht en andere vertelsels.

Helder uiteen gezet door dr. Paul Cobb, prof Islamic History aan de University of Pennsylvania.

meer:

Penn Museum en op youtube

dr. Paul M. Dobb

Labels:

1001 nachten,

lezing,

literatuur,

Paul M. Cobb,

video

2.26.2017

2.25.2017

Vi azoy lebt der kayser?

Op deze koude doch fraaie zaterdag, een muzikaal intermezzo.

Paul Robeson brengt een prachtig stuk uit de Jiddische volksmuziek.

voor de meezingers onder ons:

tekst uit jewishfolksongs.com

Paul Robeson brengt een prachtig stuk uit de Jiddische volksmuziek.

voor de meezingers onder ons:

| Rabosay, rabosay, khakhomim on a breg, | Gentlemen, endlessly wise, |

| Kh'vel aykh fregn, kh'vel aykh fregn, | I want to ask you a question. |

| - Nu, freg zshe, freg zhe, freg, | - Nu, ask, ask, ask: |

| Entfert ale oyf mayn shayle: | Everybody answer my question: |

| Vi azoy trinkt der keyser tey? | How does tsar drink tea? |

| Me nemt a hitele tsuker, | You take a cylinder of sugar, |

| Un me makht in dem a lekhele, | And carve a hole on the top, |

| Un me gist arayn heyse vaser, | And into it you pour hot water |

| Un me misht, un me misht ... | And then stir and stir. |

| Oy, ot azoy, oy, ot azoy, | Oy, just like that, oy, just like that, |

| Ot azoy trinkt der keyser tey! | That's how the tsar drinks tea. |

| Rabosay, rabosay, khakhomim on a breg | Gentlemen, gentlemen, endlessly wise, |

| Kh'vel aykh fregn, kh'vel aykh fregn. | I want to ask you a question. |

| - Nu, freg zhe, freg zhe, freg. | - Nu, ask, ask, ask: |

| Entfert ale oyf mayn shayle: | Everybody answer my question: |

| Vi azoy est der keyser bulbes? | How does the tsar eat potatoes? |

| Me nemt a fesele puter | You take a barrel of butter |

| Un me shtelt avek dem keyser oyf der anderer zayt, | And you place it opposite the tsar |

| Un a rote soldatn, mit harmatn, | And a company of soldiers, with cannons, |

| Shisn di bulbes durkh der puter | Shoot the potatoes through the butter |

| Dem keyser glaykh in moyl arayn ... | Straight into the tsar's mouth. |

| Oy, ot azoy, oy, ot azoy, | Oy, just like that, oy, just like that, |

| Ot azoy est der keyser bulbes! | That's how the tsar eats potatoes. |

| Rabosay, rabosay, khakhomim on a breg, | Gentlemen, gentlemenn, endlessly wise, |

| Kh'vel aykh fregn, kh'vel aykh fregn. | I want to ask you a question. |

| - Nu, freg zhe, freg zhe, freg. | - Nu, ask, ask, ask: |

| Entfert ale oyf mayn shayle: | Everybody answer my question: |

| Vi azoy shloft der keyser bay nakht? | How does the tsar sleep at night? |

| Me shit on a fuln kheyder mit federn, | You fill a room with feathers |

| Un me khmalet ahin arayn dem keyser, | And you wham the tsar in, |

| Un dray polk soldatn | And three regiments of soldiers |

| Shteyen a gantse nakht un shrayen: | Stand all night and shout: |

| Sha! Sha! Sha! | Shah! Shah! Shah! |

| Oy, ot azoy, oy, ot azoy, | Oy, just like that, oy, just like that, |

| Ot azoy shloft der keyser bay nakht! | That's how the tsar sleeps at night. |

tekst uit jewishfolksongs.com

Labels:

Jiddisch,

muziek,

Paul Robeson,

Rusland,

Tsaar

2.14.2017

2.11.2017

2.05.2017

Walatta Petros, een antikoloniale heilige

Op deze fraaie zondag brengen we u het verhaal van de Ethiopische heilige Walatta Petros.

Een fascinerend verhaal:

bron: History Today

Een fascinerend verhaal:

The 17th-century saint Walatta Petros was not the sweet and gentle angel that many might imagine when thinking of a holy woman. This Ethiopian leader was fierce, more given to reprimanding her devoted followers than comforting them and not above killing those who disobeyed her. It is not surprising, then, that she controlled the fate of kings.

When the Jesuits came to Ethiopia in the late 1500s, they managed to convert the Ethiopian king Susenyos from the Ethiopians’ ancient form of Christianity to Catholicism and, in 1622, he commanded his subjects to do the same. Enraged, Walatta Petros went round the country to preach against him and his ‘filthy faith of the foreigners’, barely surviving the persecution of the king’s soldiers, the rebuke of his court, attempted rape by her jailer, the perils of desert exile and the propaganda of the Jesuits. She, and the many noblewomen who joined her in refusing to convert, eventually succeeded in forcing Susenyos to rescind his conversion edict in 1632, thus ending a civil war and returning the country to the Ethiopian Orthodox Tawahedo Church.

As the art historian Claire Bosc-Tiessé argues, Walatta Petros’ monastic community was, in addition to being a centre of orthodoxy and a home for powerful abbesses, an asylum for rebels against the king. Following her death in 1642, legends grew up about the miracles she performed over the centuries to protect those in danger from kings.

We know about these legends from two relatively new parts of the saint’s hagiography, added in 1769 and 1870 to the original text, which was first written down in 1672 in Ge‘ez, an Ethiopian classical language. This hagiography, the Gadla Walatta Petros (Life-Struggles of Walatta Petros), is actually a composite text of four different sections: the gadl (the saint’s life), the ta’amer (the saint’s miracles), the malke’ (a long poem praising the saint from head to toe) and the salamta (a short hymn praising the saint’s virtues). The miracles, the ta’amer (literally, ‘signs’), are not those that were performed while the saint was alive but the ones that happened after her death, when followers called upon her to intervene and grant their prayers. The problems she solved generally have to do with physical danger, whether from illness, animals, hunger or attackers.

In Ethiopia, miracles can be added to a saint’s hagiography over the years. Two manuscripts of the Gadla Walatta Petros, for example, include miracles that the saint performed posthumously for those escaping a succession of kings across the 18th and 19th centuries. In them, Walatta Petros not only protects her community from the persecution of kings, she teaches disrespectful monarchs to fear her. Thus this hagiography – the earliest known book-length biography devoted to the life of an African woman – documents not just a remarkable life but also Ethiopians’ belief that women can – and do – shape history.

In her hagiography, some kings take the saint seriously from the first. Just a few months after Susenyos rescinded his conversion edict, he died. His son Fasiladas came to power and presided over the newly restored ‘right faith’. The new king had long been a friend of Walatta Petros and, in 1650, he granted land and goods in order to establish a permanent monastery for her community.

Cattle dancing

The legend of Walatta Petros quickly rose in eminence. She appears in the royal chronicles of various kings. In 1693, for example, the king consulted the leaders of her community about the suitability of a new head of the church. And again, in the 1730s, a chronicle relates a vision Walatta Petros had that legitimated the reign of the current king, Iyasu II (r. 1730-55, the great-great-grandson of Susenyos). The chronicle depicts Walatta Petros on her way to the Ethio-Sudan borderlands, banished into exile in the 1620s by an angry Susenyos. In a dream, she saw cattle dancing in front of Iyasu’s great-grandmothers on both sides, thus predicting that their line would yield a son who would lead the nation. In this, her ability to fight heretical kings had transformed into an ability to identify just kings.

Other kings were slower to understand that Walatta Petros was a figure to be feared. Indeed, quite a few of the miracles depict kings ignoring her messages to them – to their peril. For instance, in the late 1720s, a group of rebels rose up against King Bakaffa, the great-grandson of Susenyos. According to her miracles, more than 2,000 rebels sought refuge at Walatta Petros’ monastery. When Bakaffa learned where they were, he dispatched troops to the monastery with orders to kill everyone there, including the monks and nuns. An enraged Walatta Petros appeared to Bakaffa in a dream, demanding that he reverse his orders. Bakaffa, frightened, woke up but then fell asleep again. Twice more, Walatta Petros delivered the same message and finally, in the last dream, she cast him from his throne and set it on fire over him. The terrified Bakaffa then began to suspect that Walatta Petros was not merely a dream figment but was actually speaking to him. He summoned a nun who had met Walatta Petros over 60 years before, who confirmed that the woman he described was indeed the saint. Finally heeding her warning, Bakaffa sent a swift-running messenger after his army to tell them to turn back instantly. Everyone at the monastery was saved. According to her hagiography, a king who was so powerful that he had not hesitated to execute a noble rebel in front of his entire camp quaked at the thought of Walatta Petros’ indignation. The power of her reputation was enough to subjugate kings as well as to validate their reigns.

Miracles and wonders

Much later, Walatta Petros protected her community from another king, Tewodros II (r. 1855-68), known in British history for taking European missionaries and British government representatives hostage and forcing them to build him a cannon. In the miracle, he is called Tewodros Me’rabawi, the western Tewodros, probably because of this association. His miracle involves, perhaps predictably, a cannon. An earlier king, Takla Giyorgis I (r. 1779 and 1800), had seized a cannon in battle, which he then donated to a church in the capital dedicated to Walatta Petros. The cannon remained there until Tewodros became king when, in an effort to assert his authority, he issued a decree saying that those found to possess cannons or firearms should have their houses pillaged and their possessions seized. The cannon in her church was found and confiscated, the priests were taken into custody and Walatta Petros’ feast day was cancelled. But, due to the miraculous intervention of Walatta Petros, when the cannon arrived at court, it disintegrated. When Tewodros realised what she had done, he immediately set the priests free to save himself from her wrath. The miracle concluded with the words: ‘In just this way does Walatta Petros still work miracles and wonders.’ Even Western technology was no match for her.

Before Walatta Petros was born, her father had a vision of her future, in which ‘the kings of the earth and the bishops will bow to her’. Susenyos was Walatta Petros’ mortal enemy – condemning her, calling her before a tribunal, ordering her to undergo re-education by the Jesuits, exiling her and only narrowly avoiding killing her – but, when he rescinded his conversion edict, her hagiography claims, he also sent Walatta Petros a message informing her of his change of heart, hinting that he regretted his actions. Walatta Petros’ relationship with Susenyos’ progeny seems to echo this shifting relationship from disrespect to obedience, all learning to fear her.

Walatta Petros continues to be revered as a saint to those who resists authority and are dedicated to the pursuit of peace in the world.

bron: History Today

Labels:

anti-kolonialisme,

Ethiopië,

heiligen,

history today,

missionering,

Tawahedo,

Walatta Petros

2.04.2017

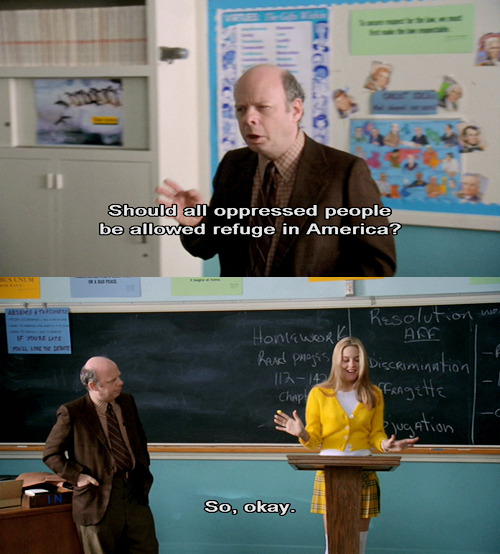

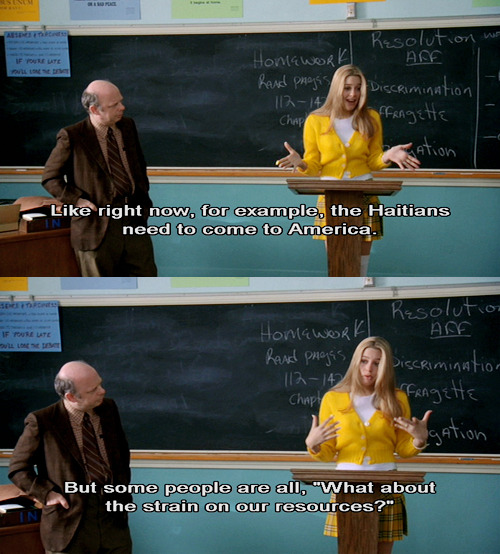

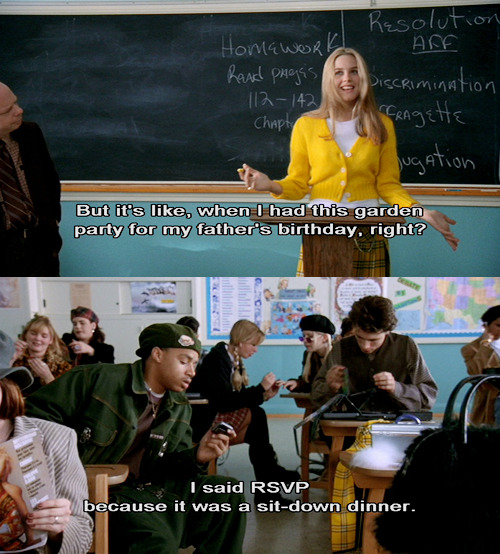

'if the governement could just rearrange some things'

beste vrienden, vandaag gaan we het hebben over de zogenaamde vluchtelingencrisis.

90s teenflic Clueless geeft ons een belangrijke les in het omgaan met vluchtelingen.

solidariteit, menselijkheid, broederschap, herverdeling, planning, sleutelbegrippen.

90s teenflic Clueless geeft ons een belangrijke les in het omgaan met vluchtelingen.

solidariteit, menselijkheid, broederschap, herverdeling, planning, sleutelbegrippen.

Labels:

Alicia Silverstone,

Clueless,

vluchtelingen

2.02.2017

Abonneren op:

Posts (Atom)