William Langland’s 14th-century poem Piers Plowman opens with a vision, witnessed by a dreamer as he slumbers on the Malvern Hills. He sees before him a ‘fair field full of folk’, of many classes and professions, ‘working and wandering as the world asketh’ – a vision of the whole of human society. But almost the first thing he realises is that this labour is not fairly distributed: some people work hard yet barely have enough to eat, while others selfishly squander what the labourers toil for.

A wise teacher appears and explains to the dreamer that the root of this injustice is greed. Over-consumption by some people means there isn’t enough to go around, she says; the bountiful resources of the earth can provide enough for everyone, but only if people do not consume more than they need. Her solution is to remember that ‘measure is medicine’: moderation is healthy for the soul and the body, for the individual and for society at large.

In a time when famine was a real danger, this poem’s anger about immoderate consumption and waste of food was a challenging response to a pressing social problem. But Langland’s radical poem is concerned with injustice of all kinds and greed forms part of its diagnosis for many contemporary social ills, including corruption in the law, government and church. Over-consumption and excessive desire for anything, even things good in themselves, can cause problems – not only food but money, power and pleasure, too.

This poem speaks to our own time as boldly as to the problems of the 14th century. Almost every day seems to bring a news story about attempts to reign in over-consumption: plans to help the environment by banning plastic or taxing red meat, or discussions about whether we should all be trying to limit our screen time and consumption of social media.

The problem is, as Piers Plowman goes on to explore, solutions imposed from outside can only do so much. Moderation has to come from within, but it demands a self-control which is difficult to learn. Over centuries, the medieval church had developed practices intended to help believers confront and master the gluttonous desires of the human heart: confession, penance and voluntary self-denial, aiming to teach people to rule their desires rather than be ruled by them. But Langland’s fierce satire shows how even those practices could become corrupted; perhaps we should not set too much store by so-called ‘sin taxes’, either.

Most striking is how the poem unites its concern about waste and excess with the dangers of squandering more intangible resources: time and words. The dreamer is warned that ‘spilling’ time and speech mindlessly is about the worst thing you can do. Each person’s time, after all, is a finite resource: we only have a certain number of hours in our lives, so it matters how we choose to spend them.

Wasting words is still worse, the dreamer is told, because speech is precious, even sacred. To make this point, the poem describes speech with a series of beautiful metaphors: it is a joyous ‘game of heaven’ and a ‘spire of grace’, a green shoot alive with possibility and hope. Words are imagined as ‘God’s gleeman’ (‘minstrel’) and his musical instrument, a ‘fiddle’, which needs to be tuned and tempered properly before it can make the music for which it was designed. These metaphors imagine words as a source of delight and pleasure. It is because they are so beautiful and powerful that it is wrong to waste them.

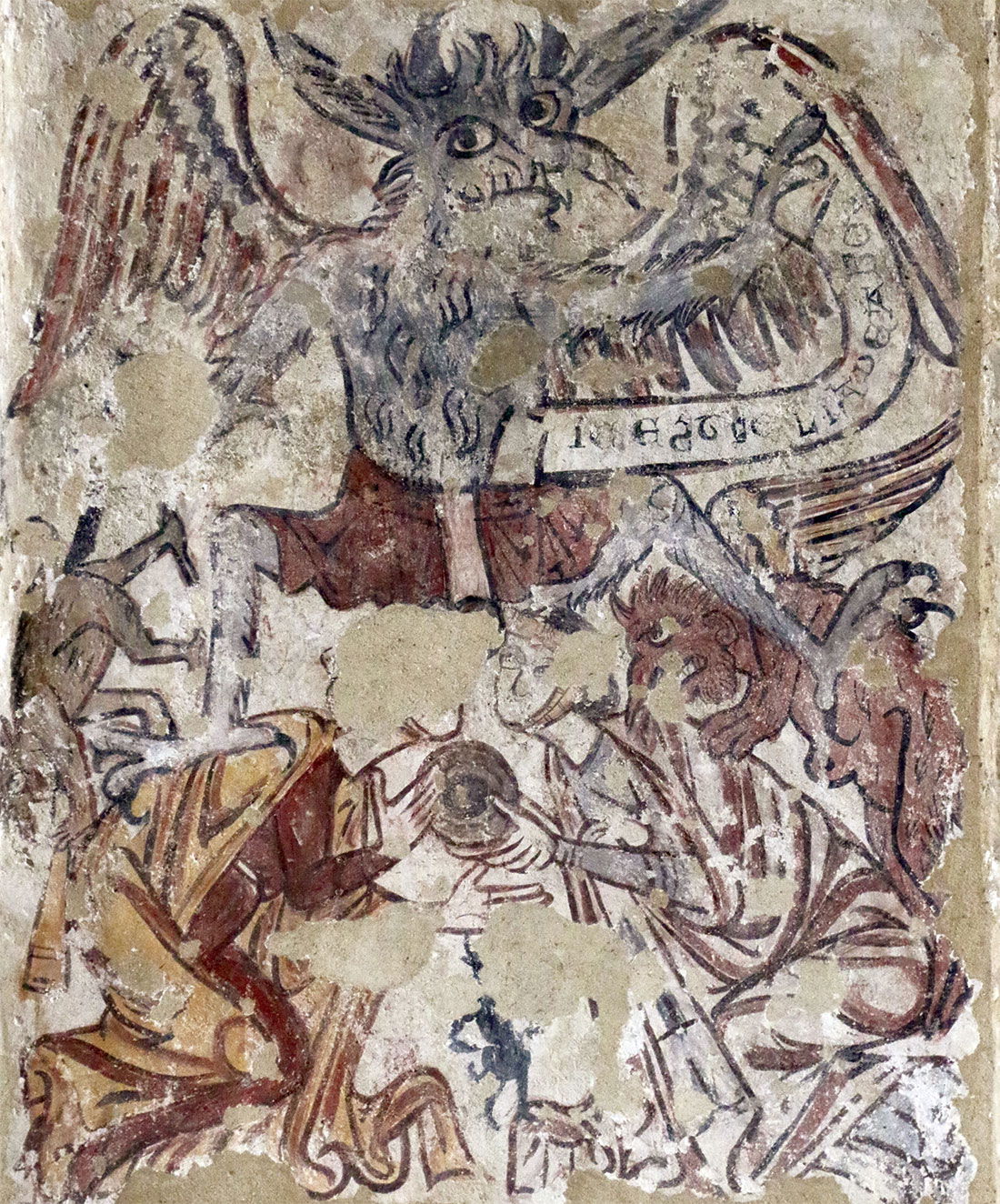

This poem’s concern with wasteful words is part of a wider conversation in medieval society about the misuse of speech. Many medieval writers condemn what they call ‘janglers’ – an expressive descriptor for people who use words in a wasteful or destructive way, by idle chatter, spreading gossip and slander, or by hurting other people. This concern was personified by the story of the devil Titivillus, a demon whose speciality was keeping track of sinful words. He was said to go around the world collecting idle words (and even scribal errors, the medieval equivalent of careless typos) and gathering them up in a sack, so that their speakers could be held accountable for them at Judgement Day. This, too, feels disconcertingly timely: what would Titivillus collect today but hasty, intemperate, or ill-considered tweets?

Geschreven door Eleanor Parker, docent middeleeuwse Engelse literatuur aan Brasenose College in Oxford en verschenen in History Today Volume 69 Issue 3 March

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten